First photography. Niépce.

This morning, a friend of mine called me, and as always, our conversation revolved around Photography, Audiovisual Arts (CINEMA), Art in general, and occasionally, other less interesting but still important topics. Our calls usually last around an hour and a half, almost two hours, which, by the way, just "fly by." They feel like mere minutes.

During our conversation, the topic of how certain people advocate for chemical photography came up, with the reasoning, perhaps, that it is a more ecological process or less invasive to nature. After all, it doesn’t involve plastics or electricity as digital photography might.

Beards, suspenders, and a pair of leather boots.

One of the key points of our engaging conversation centered around the production of chemical film, and of course, being naturally curious, I started researching to explain, at least on a surface level, how this photosensitive element, so widely used for almost a century, is manufactured.

This is where Mr. George Eastman and his company, Eastman Kodak Company, come into play. They are practically responsible for the democratization of photography, allowing every household to own a camera. And all of this because photography is not vegan.

Although this might seem like a jab at veganism, it isn’t. It's simply a historical... and chemical fact about how photosensitive films for chemical photography are made.

Characteristics of Photographic Film.

The first characteristic needed is flexibility; after all, the film must endure multiple exposures, and the most practical way is for it to roll up on itself, occupying minimal space. Can you imagine lugging around a camera and having to carry 36 photographic films to make 36 exposures? You really had to think about your shots. Well, unless you were shooting in Large Format, then it wasn’t necessary. Finally, we could shoot in "machine gun mode" without intention.

On the other hand, the photosensitive chemical compounds must be stable and be in a medium that also provides stability.

But what are we talking about? The main photosensitive elements were silver halides. In chemical terms, we’re talking about Silver Bromide (AgBr) and Silver Chloride (AgCl). Both have the unique property of changing their oxidation state when absorbing light photons. This is a desirable trait for any application where we want to harness light. For example, photochromic glasses usually (or used to) contain silver halides that darken upon exposure to light photons. It's not my intention to dive deep into these chemical reactions to avoid confusing the reader, who might not have exhaustive knowledge of chemistry.

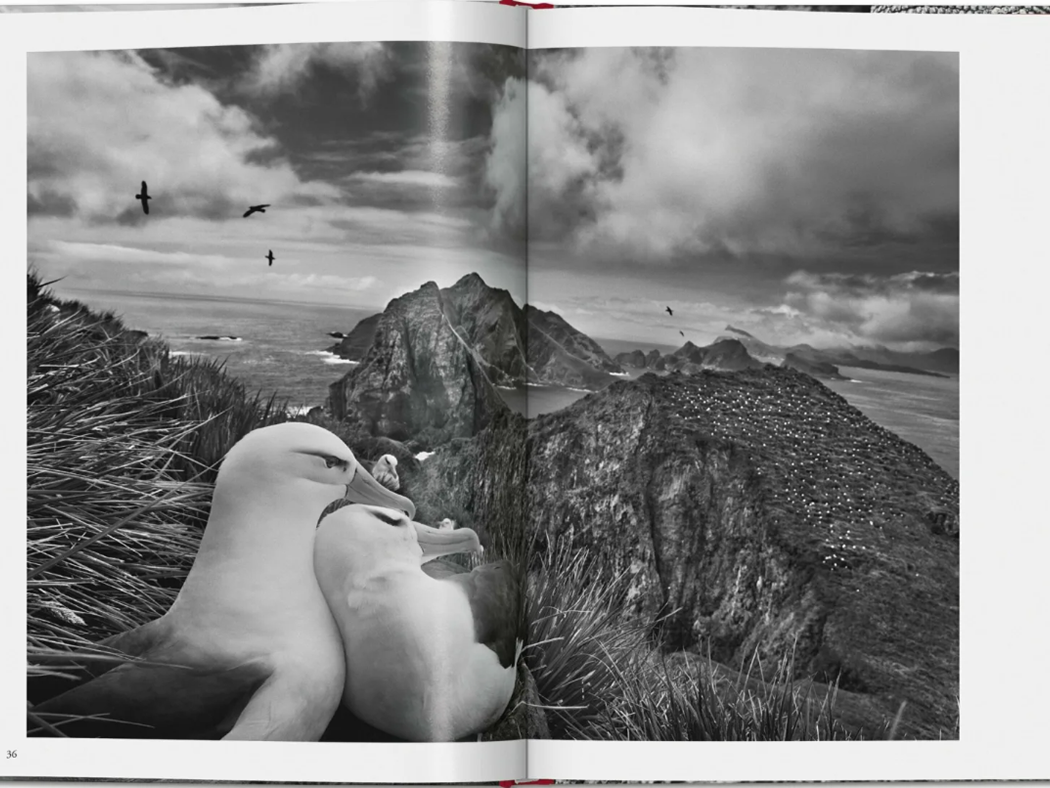

Photography is essentially a chemical-physical application where the predominant reaction is an interaction between a photosensitive element and light. Put another way, it captures areas of light and shadow to be imprinted on a physical medium. Of course, this is from the perspective of the application itself. However, photography as an art form goes much further, which we can discuss in other articles.

These silver halides we mentioned had to be embedded in the film with a “fixative,” so to speak, and that's where emulsions come into play. Some tests were done with liquid colloidal emulsions using another sensitive agent like silver nitrate (AgNO3). However, these liquid solutions were time-consuming and made the process quite complicated for the photographer, or rather, the lab technician.

Eastman adopted some improvements thanks to suggestions from Charles Bennet (a photographer), where the process shifted to a dry emulsion. In this case, a silver halide, specifically bromide (AgBr), was used in a gelatinous emulsion, which was then dried, resulting in a photosensitive film that was easy for photographers and lab technicians to handle.

This led to a patent and later commercialization, laying the groundwork for photography as a more democratic form of expression among the population.

Later improvements came from the supports, moving from metallic ones (like in the Daguerreotype) to glass, and later to acetates, celluloses, nitrocelluloses, and finally polymer derivatives. The silver halide crystals were also improved to enhance exposure times through higher sensitivity, meaning that chemical purification processes were improved.

Once again, chemistry saves the world.

Now the question arises, where does this gelatin come from? Gelatin is the natural form of collagen, which is found in animal bones, among other parts.

The animal rights organization PETA reported that leading companies in photosensitive photographic material used cows to extract collagen and/or gelatin from them to make their consumer products. Some sources and reputable newspapers claimed that some of these companies had cattle slaughterhouses at their disposal for extraction.

That’s why chemical photography, as the title of this article suggests, wasn’t vegan.

Its alternative, digital photography, isn’t necessarily better for the environment either. After all, many materials used today, including plastics and metals like lithium for batteries and other metals like tantalum, are highly polluting and harmful to the environment. Upon saying this, perhaps the first thing that comes to mind is electric cars... but that’s another story.

However, I must be honest with you, dear reader, and tell you that I haven’t been able to find an official source from one of these companies publicly confirming the possession of slaughterhouses. Understandably, given that these companies are constantly being sued by organizations.

Finally, I can affirm that no cows were harmed in the making of this article.

Bibliography:

-American Chemical Society. (n.d.). Landmark Lesson Plan: Eastman Kodak and the Invention of the Brownie Camera. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/eastman-kodak.html#better-film

-Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Gelatin process. In Britannica.com. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/technology/gelatin-process

-Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Gelatin. In Britannica.com. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/gelatin

-Kodak. (n.d.). Chronology of film. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.kodak.com/en/motion/page/chronology-of-film/

-PETA. (n.d.). Does film contain gelatin? In PETA.org. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.peta.org/about-peta/faq/does-film-contain-gelatin/

-Quimica.es. (n.d.). Sales o haluros de plata. Retrieved August 9, 2024, from https://www.quimica.es/enciclopedia/Sales_o_haluros_de_plata.html

-Marshall, C. (1999, January 18). Company grinds cow remains, but keeps costs close to the bone. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB916612340706719000